Ontology is the philosophy of reality, of existence and being and becoming. You might think that this must be one of the most unnecessary parts of the intellectual life, and you might be right. It is, however, a valid philosophical subject, and it does have a relationship to the philosophy of science. A little journey down memory lane might show why.

Albert Einstein was a bit unhappy in 1935. He had published his theories of special relativity in 1905 and general relativity in 1915. He became famous after a solar eclipse in 1919 demonstrated gravitational bending of light exactly as predicted by general relativity. He really didn’t like the popular “theories of relativity” moniker on the grounds that he had really demonstrated what was absolute, namely the speed of light in vacuum. But that was not what made him unhappy.

No, he was unhappy because he could not reconcile relativity with that other new physical theory of his age, quantum mechanics. He intuited there was also something wrong with quantum mechanics.

Quantum mechanics began as an attempt to understand how atoms absorbed and emitted energy, why certain atoms for example emitted light of one color but not another. Then the discovery of radioactivity led to the discoveries of atomic decay and sub-atomic particles, which led to even more discoveries about the structure of atoms. Einstein was very familiar with the tools of statistical mechanics, he had helped to advance the subject himself (he proved the existence of atoms in this way by studying the Brownian motion of particles suspended in fluids), but the sheer albeit statistically predictable randomness of quantum mechanics raised philosophical questions about the nature of reality itself. He summed up his disquiet in the phrase “God does not play dice.”

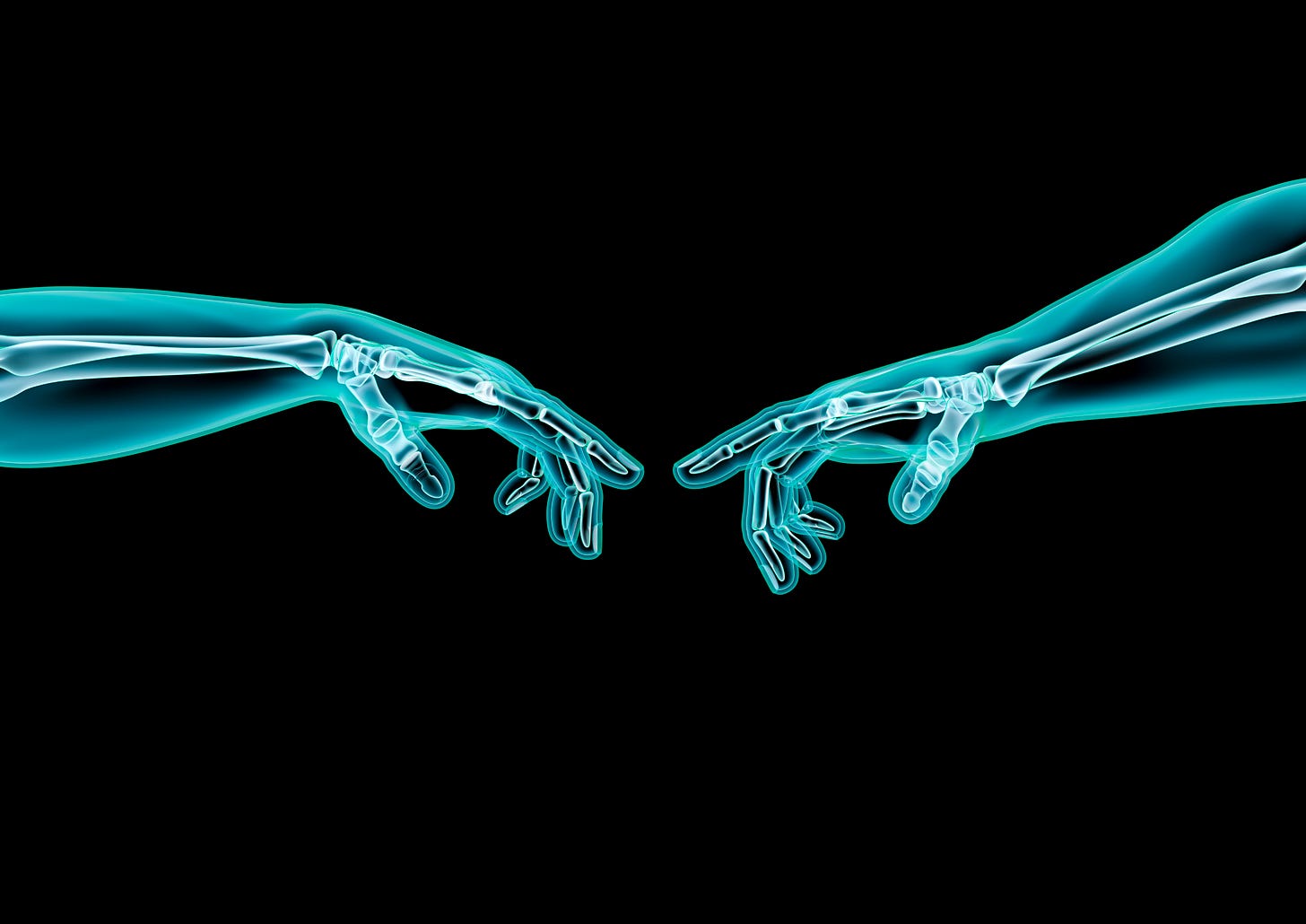

So, in 1935 he and Boris Podolsky and Nathan Rosen published a paper titled Can Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical Reality be Considered Complete? In it they argued that quantum mechanics must be incomplete because, as it was then understood, it allowed for a kind of faster-than-light signaling between particles that had been entangled at the time of their creation. Such signaling violated special relativity, so therefore it was impossible, and therefore this quantum mechanical prediction was wrong. Einstein and Podolsky and Rosen were defending what is now called local realism, and Einstein derided non-localism as “spooky action at a distance.”

This ‘thought experiment’ became known as the “EPR Paradox” and physicists tried to confirm or refute it for years afterwards. Then in 1964 John Stewart Bell published what became known as Bell’s Theorem. Bell created what became known as Bell’s Inequalities, which allowed for ways to test the EPR Paradox. He also made a startling statement: in effect, quantum mechanics says that faster-than-light signaling, non-local “spooky action at a distance”, must happen or else the universe is not real.

The reaction to Bell’s Theorem was, to say the least, interesting. Some scientists reportedly concluded that Bell was right, and Einstein was right, and therefore the universe was not real.

Now, just think that over for a minute.

Here we see some very smart people decide that nothing is real. Not the universe, not their field of study, not their published papers, not their earned degrees, not their blackboards and computers and particle accelerators, nothing. They themselves and everyone they love is not real.

Put aside the problem of how Bell’s Theorem itself could be unreal, which leads to an infinite regression of unreality.

Ontology has various ‘schools’ on the subject of unreality. There is an antirealist school that maintains it is impossible to know if anything exists at all – you think you can prove it, but you really can’t.

Then there is an instrumentalist school that claims our observations determine reality. This is fairly reasonable as a statement of perceptional limits, and it can be a source of humility when it reminds us to not make hard assumptions about things we cannot yet observe. But to carry this farther, to the point where out of sight out of mind is the rule that tells us how to think (or not think), is very limiting to the human imagination. It limits the scientific imagination as well.

One way or another, these rabbit holes look remarkably alike from a realism viewpoint. We can wonder why anyone would be attracted to such ideas. Avowing reality seems so much easier.

So, did physics fall into a mental black hole and did physicists all breakdown in despair?

Not at all.

Obviously, scientists were able to deal with conflicting ideas, just as most of us do with incomplete information. Bell might be right, and Einstein might be right, but conflict between the two need not drive anyone insane. We will see the truth of this again and again in these essays. It is even possible that they were just joking about the universe not being real, but if they were joking the popular science writers of the day didn’t notice.

Then a series of laboratory experiments termed Bell tests demonstrated faster-than-light “spooky action at a distance” signaling, first in 1972, more certainly in 1983, and without any loopholes in 2015. It has been seen and measured. Local realism still reigns in the non-quantum world, it is not overthrown, but non-local realism is true also.

Relativity and quantum mechanics remain unreconciled to this day.

And upon further reflection, it was realized that the non-local “spooky action at a distance” signal is random, and therefore does not violate relativity. Einstein and Bell were both right, Einstein had merely misunderstood the mathematical nature of the signal. It turned out the postulates and methodology of the EPR Paradox had immense value to science, even though its conclusion was wrong.

The belief, triggered by John Bell, that the universe was not real is long forgotten.